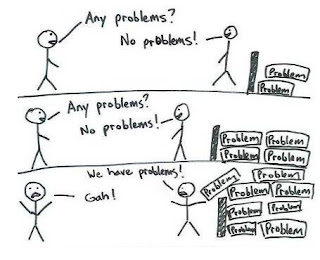

Q: What do you do when something goes (seriously) wrong in your day to day operations?

A: Use a standard Closed Loop Corrective Action (CLCA) process. CLCA characterizes the problem, contains the problem, implements corrective action, identifies and addresses root cause, and verifies problem resolution.

In times when things in my operations don't go as expected, I rely on this standard approach for reacting fast and effectively. This CLCA process is part of my standard work as a manager and an add-on to standard A3 problem solving. The attached image includes a simple CLCA template. Here are the "5C" steps in the CLCA process:

1. Characterise the problem and get the right team togetherTo start with, establish a small group of people with the process and/or product knowledge, allocated time, authority, and skills to address the issue.

Now the problem or issue needs to be carefully defined and bounded by describing the issue and its impact. Tips for describing the problem are: analyse existing data, observe the place where the problem occurred (gemba), establish an operational definition, use 5WH (who, what, when, where, why, how), be specific, establish the extend of the problem (measurable).

Example 1: You have suffered a severe sun burn

Example 2: A number of PC's with a wrong configuration has been shipped to customers

2. Contain the issueOnce a problem becomes apparent there has already been some loss suffered, either by a customer or internally by one or more departments. Immediate action needs to be taken to 1) prevent harm (economic or physical) to additional customers or departments and 2) correct the mistakes that have been made. Containment action planning must begin as soon as a problem becomes known.

Example 1: Getting out of the hot sun and going to the doctor for treatment of a severe sun burn, and cool the skin with water.

Example 2: Stop shipping more PC's with incorrect configuration and ensure the impacted customers will receive the correct PC.

3. Identify the Root CauseWhile it's desirable that corrective action be taken as quickly as possible, it's just as important that the true root cause of the problem is identified and fixed. Sufficient time should be spent in causal analysis so that the problem is fixed once, and stays fixed.

Example 1: Extended exposure to direct sun light caused severe sun burn

Example 2: The PC product configuration information on marketing material and on the online store feed from different data sources which are manually synchronized. The manual work is prone to error.

4. Corrective and preventive actionIn this phase, interim and permanent actions are taken to deal with all of the problems that a) have occurred and b) similar problems that can be prevented. Corrective action is the implementation of a solution believed to eliminate the root cause of an observed problem, defect or failure. Preventive action means applying the solution to prevent a similar problem from happening in similar processes and products. In cases where the problem impact is high and the permanent solution complex, a Kaizen event or BPI project can be initiated.

Example 1: Putting on sun screen on yourself to prevent sun burn and putting on sunscreen on your children.

Example 2: Use one source for product configuration data to feed the marketing material and webstore.

5. Closure Closure means verifying by means of data and observations that the problem has been solved and improvement are standardized and sustainable.